New visitors to the Gebbie Speech, Language and Hearing Clinic in the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders sometimes don’t even notice the new videonystagmography (VNG) system when they walk into the examination room. That is understandable, as its low-profile presence on a countertop suggests nothing more complicated than a printer. They would pause a bit, however, if they knew just how important this equipment was to patients and the students who learn at this center.

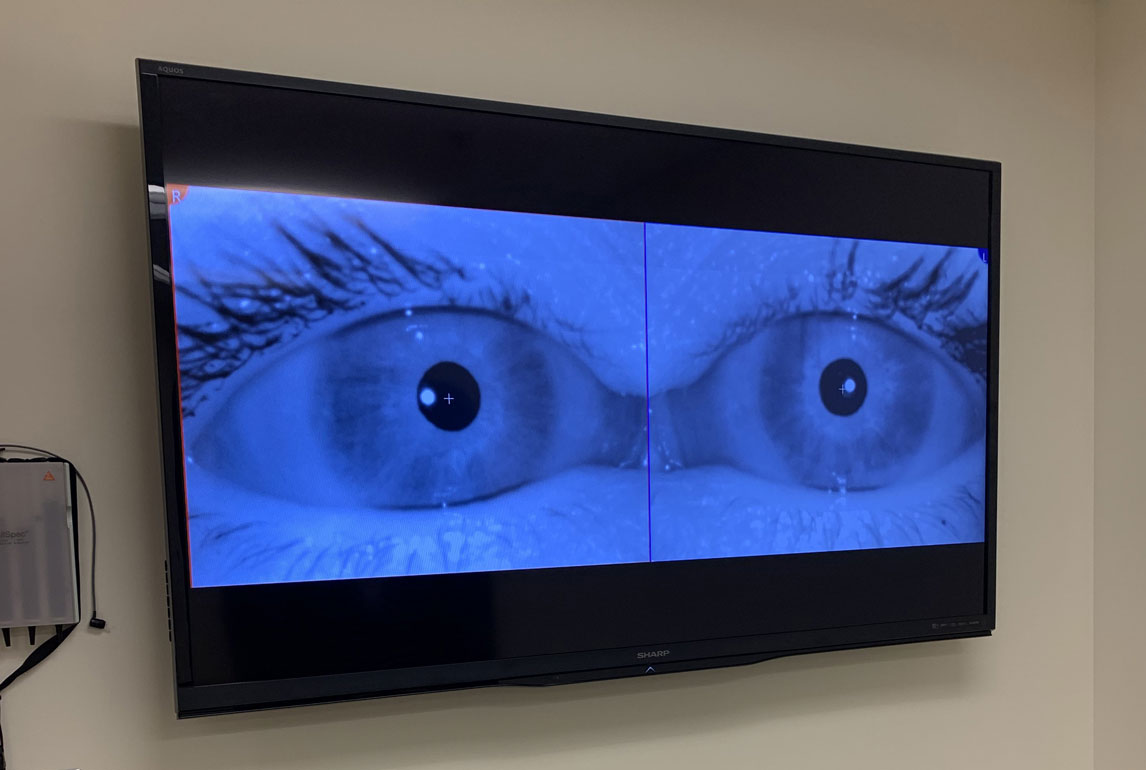

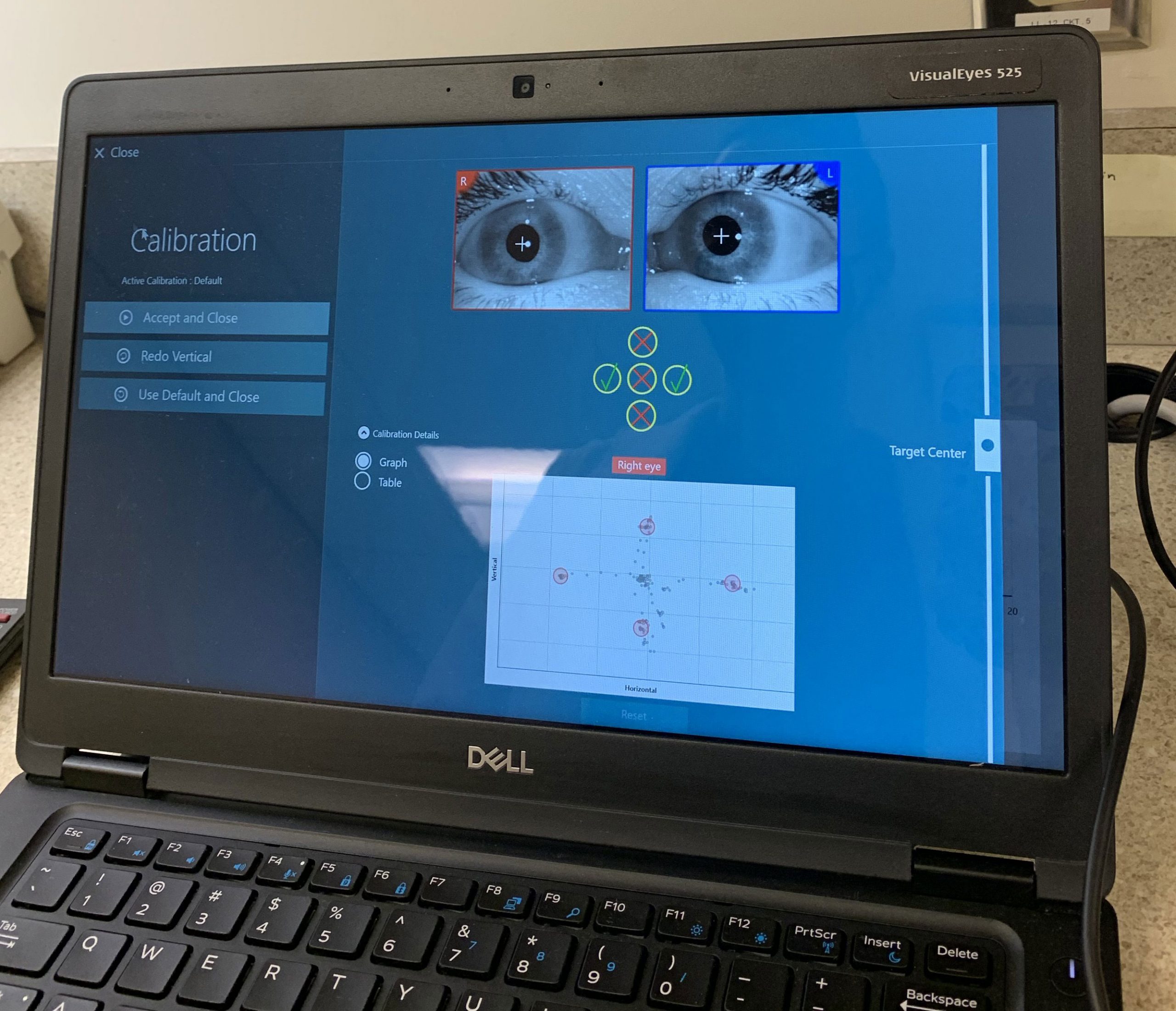

A patient undergoing tests using the Gebbie Clinic’s new videonystagmography (VNG) system.

The VNG system was made possible through a gift given last year by Whitman alumnus George Knight ’81 in honor of his late wife Kimberly, who received a master’s degree in audiology from the University in 1982. The state-of-the-art equipment—perhaps the only one of its kind in Central New York—also includes a 60-inch wall-mounted monitor, indispensable for teaching purposes, and a motorized exam table that allows for positioning of patients being tested—not just a consideration of comfort, but crucial, as the varying positions are part of the diagnostic exams.

“We are so grateful to George Knight, who has made generous donations to the Gebbie Clinic for years in remembrance of his wife, Kimberly,” says Kathy Vander Werff, professor of audiology and chair of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. “He reached out because he wanted to donate something bigger that would be really beneficial to our clinic. He’s been a tremendous support, and we have really expanded our services and how we can train our students as a result.”

The Gebbie Clinic opened in 1972 as a center for research in communication sciences and disorders. The clinic offers services to the Central New York community while also training graduate students enrolled in the Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology programs. The new VNG system underlines the cutting-edge diagnostic and treatment services the Gebbie Clinic offers to the community that aren’t widely available in the area.

The VNG equipment performs a series of diagnostic tests of the vestibular system, the parts of the inner ear responsible for balance. Interestingly, the first thing a patient undergoing vestibular testing does is put on a pair of goggles, which brings an image of their eyes to the monitor.

Wait: Eyes? For tests of the inner ear?

“Balance has to do with integrating sensory input from the eyes, ears, muscles and joints,” says Vander Werff. “We can’t see the inner ear directly, but we can get a window into how the visual and vestibular system are working together.”

Many patients visiting a hearing clinic are not there for hearing problems, but because of dizziness issues.

“Dizziness is the number one complaint at a primary care physician’s office for older adults, and if you look at all ages, it’s a top-three complaint. It’s an expense for the medical system and a serious problem in society,” says audiologist Stefania Arduini, Au.D., who does vestibular diagnostic testing at the Gebbie Clinic and teaches a vestibular audiology course for students in the clinical doctor of audiology program in the department.

According to Arduini, dizziness leads to falls. For an elderly patient with an ear problem who falls and breaks a hip, it can be very difficult to bounce back.

“With this equipment, we can do ocular motor tests that look at eye movements,” says Arduini. “We can test for positional dizziness, dizziness that comes on in certain positions. Some people have a crystal issue, where a crystal becomes dislodged in the ear; we can test and then treat for that problem. Lastly, we have the gold standard test that has withstood the test of time, the caloric test (response to heat or cold), which looks at weaknesses in the inner ear’s semicircular canals, another main cause of dizziness. All of those tests can be done with this new piece of equipment.”

The new VNG system replaces outdated equipment and allowed for the clinic to expand its diagnostic services and teaching opportunities. This current system can be connected to other existing equipment, making for a complete test battery and the new monitor means that a room full of students can watch every step.

The VNG system projects a view of the patient’s eyes onto a large screen so researchers can track eye movements.

Arduini demonstrates one of the tests that her patients might undergo. Her volunteer dons a pair of goggles and her eyes suddenly appear on the monitor, huge and slightly otherworldly, due to the projection removing the nose and positioning the eyes directly next to each other. A dot appears on the screen, and the volunteer is told to track it with her eyes as it bounces around like a rubber ball on a squash court. Meanwhile, Arduini is watching the computer to chart the eye motions. “With this particular test we’re looking for information on the functioning of the central nervous system,” she says. Students watching this exam would be able to see all the moving parts clearly, due to the size of the monitor.

They move on to an optokinetic test, which looks at the peripheral and central vestibular systems. As the screen depicts a cartoon of a village that moves ahead horizontally—similar to a video game like Super Mario Brothers.—the volunteer’s eyes are scanning the motion of the scene.

Next is a test that covers a patient’s eyes and leaves them in the dark—although the computer is still able to watch and record how the eyes behave. “I’m looking for particular eye movements with no stimulus present,” says Arduini. “Sometimes if somebody has problems with balance or dizziness, particular eye movements can give us more information as to whether it’s coming from the ears versus the central nervous system.”

“Prior to this, if you saw a patient you thought could benefit from this test, you’d have to refer them elsewhere,” says Vander Werff. Unfortunately, plenty of patients without access to a clinic like Gebbie never receive this referral.

“Physicians will often assume that a patient has one form of dizziness when in fact it’s something completely different,” says Arduini. “What I see all the time is patients coming in years later, saying, ‘I’ve been doing this thing and it’s not working.’ There are copays, therapies, even though they don’t have a formal diagnosis.”

A patient undergoing tests using the Gebbie Clinic’s new videonystagmography (VNG) system.

It’s not uncommon for patients, once finally seen at Gebbie, to find that they have a completely different problem from what they’ve been treating. “We have had patients who had been told there was nothing that could be done for their dizziness for 20 years, when in fact they are candidates for vestibular rehabilitation,” says Arduini. “I’m a dizzy patient myself. I know the importance of getting a proper diagnosis.”

As if the VNG system doesn’t already sound miraculous, it is also adapting to new research all the time and allows for upgrading software to the very latest test capabilities as they emerge in the field.

“With this equipment, along with the other tests we offer, we can fully assess our dizzy patients. Not very many clinics in this area can. I’m extremely proud of that,” says Arduini.