The 'Great Divide': Understanding US Political Polarization

Americans increasingly see the country as more divided than at any time since the Civil War. Pew Research Center polling reveals a sharp rise in partisan hostility: in 2022, 72% of Republicans and 63% of Democrats viewed the opposing party as more immoral than other Americans—up dramatically from 47% and 35% in 2016.

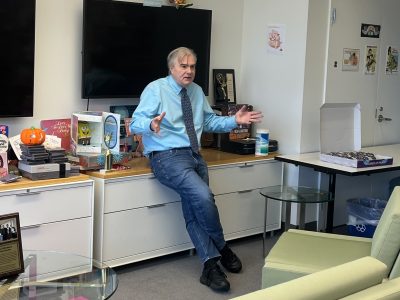

Johanna Dunaway, research director at the University’s Institute for Democracy, Journalism and Citizenship and professor of political science at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, studies this divide and its threat to democracy. Her research, supported by a 2024 Carnegie Fellowship, provides insights into how America reached this point and what recent government dysfunction reveals about our country’s political health.

Dunaway points out several key factors, starting with a fundamental misperception problem, for why America has become so politically divided.

“Much of the polarization that escalated in recent decades was largely driven by misperceptions people have about ordinary partisans on the other side—the everyday people in your neighborhood or office who happen to support the other party. The political leaders who receive the most media attention are usually the more extreme members of their party, left or right. As a result, people tend to assume ordinary partisans hold the same views as their party’s leaders. This is rarely the case except among the most extreme voters.”

Most Americans still fall closer to the center, she says. “Yet when people are asked to evaluate the opposing party, they often feel considerable animosity based on what they hear from that party’s elite and governing members. They tend to assume members of the opposing party are more extreme than they are, which creates the perception of greater policy differences between Democrats and Republicans in the public than truly exist.”

The division also results from genuine frustrations with government, the economy, and inequalities of wealth and opportunity, according to Dunaway.

“Government often seems out of touch or unresponsive, which is one reason trust in government and institutions has reached historical lows. When you combine these conditions with politically motivated leaders, charged rhetoric and a difficult-to-parse digital information environment, it becomes easy for people to blame everything they’re experiencing on the other side,” she says.

Some members of the press, political pundits and researchers have voiced the belief that politically polarized media are exacerbating the opinion divide, according to IDJC research.

Dunaway says her interpretations of the research on this issue “is that media effects exist, but they don’t work the way people often assume—with media doing all the persuading. Media in all forms respond to audience preferences and behaviors as much as the other way around. Unfortunately, the patterns of information we end up being exposed to still exacerbate divisions.”

She says the blame is tied to the economic model of today’s media landscape. “Underlying media emphasis on the extreme and outrageous is that most digital media relies on attention metrics like clicks and because competition for the public’s attention is so intense. Media outlets face strong economic incentives to publish and promote the most attention-grabbing content,” she says.

Many believe the government shutdown is evidence of partisanship beyond typical political disagreement—to the point of mutual delegitimization.

“Yes and no,” Dunaway says. “I don’t think it marks the arrival of that kind of shift. Instead, the shutdown is a symptom of the fact that we’ve already experienced that shift—from political disagreement and polarization to more serious issues like mutual delegitimization. We are, and have been for quite some time, at the point where the two opposing entities are systematically and intentionally undermining each other’s legitimacy.”

Dunaway thinks calmer voices may eventually tamp down political rancor and return more civility to public discourse.

“I think it will depend on if we can get back to the notion of all politics being local. Carnegie Corporation of New York and CivicPulse research shows that the negative effects of polarization are less evident among local public officials and local communities. Local governments are in a unique position to cooperate and compromise across party lines.

She observes: “Both local news and local politics are less polarizing than their national counterparts. Our [IDJC] research on polarized voting behavior [PDF] and affective polarization [PDF] shows local news is less politically polarizing [and] more trusted relative to national news. Because local news is more focused on local issues of more immediate daily concern rather than national politics, it contains fewer partisan cues, which tend to activate partisan sentiment.

Also encouraging, Dunaway says, is a broadening research and investment initiative to help bolster how media outlets operate and cover political news.

“The other reason for optimism is that there is broadening philanthropic interest in funding efforts to shore up local news. And in many states, there are policy efforts to address the challenges facing local news. My colleague Josh Darr’s work with our new IDJC Local NExT Lab is a perfect example of the kind of work philanthropists are helping to fund as we test different ways of restoring and supporting local news.”

The IDJC is a joint initiative of the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and the Maxwell School. It conducts nonpartisan research, teaching and public dialogue aimed at strengthening trust in news media, governance and society.