Innovative HDFS Course Prepare Students for Patient-Centered Care

In an era when artificial intelligence (AI) can aid in diagnosing diseases, serve as a virtual health assistant and help discover life-saving pharmaceuticals, there are certain irreplaceable human skills that algorithms cannot replicate.

At the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Human Development and Family Science (HDFS), students are developing empathy, cultural humility and critical reasoning through innovative courses that prepare them for some of health care’s most challenging moments.

Helping to lead this effort is Colleen Cameron, professor of practice in HDFS. Her courses, rooted in hands-on and community-engaged learning, represent a growing recognition that the future of health care depends not just on technical knowledge, but on uniquely human abilities that ease patients’ often stressful experiences.

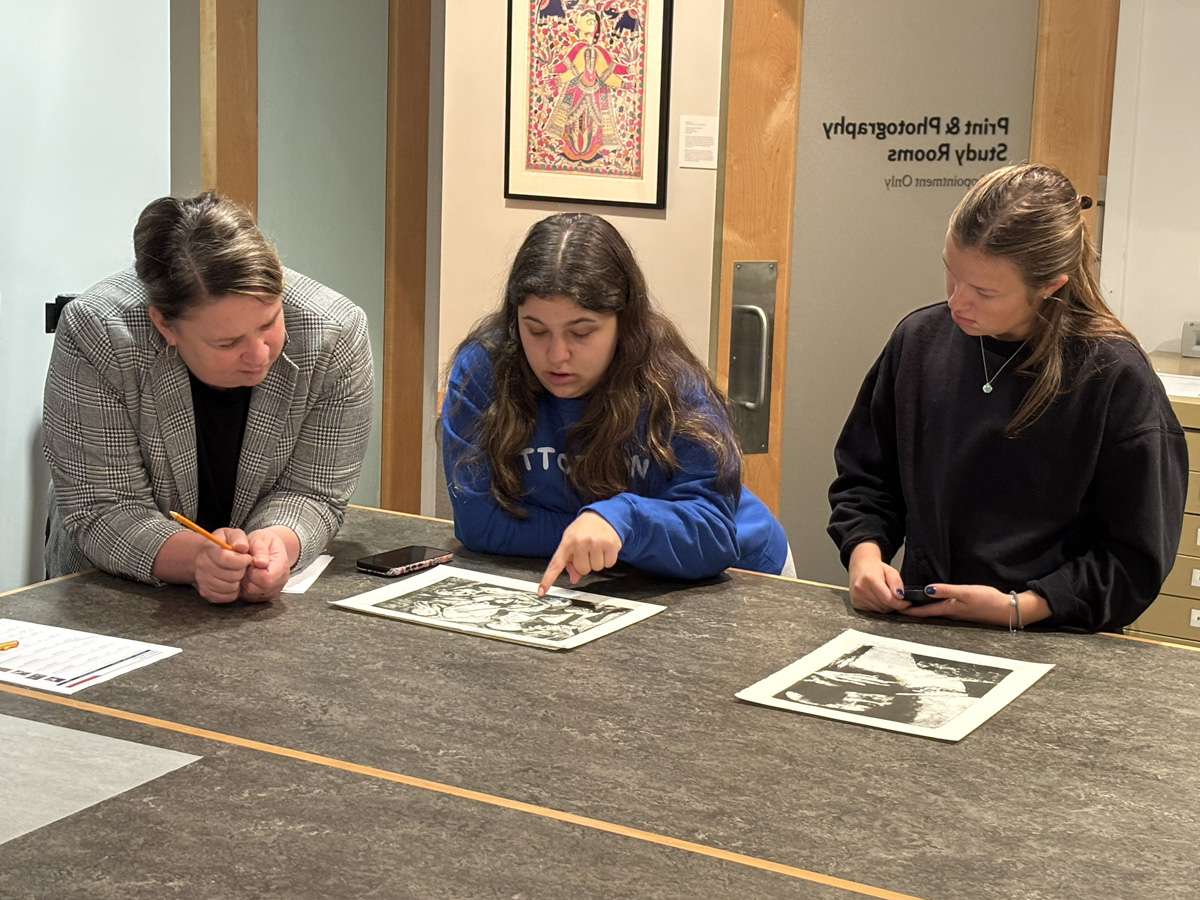

At the heart of Cameron’s classes are what’s referred to as object-based learning. This pedagogical approach uses physical or visual objects as the primary focus for teaching and educating. Instead of learning solely from textbooks or lectures, students directly engage with real objects, artifacts, artworks, specimens or other tangible materials to develop critical thinking, observation and analytical skills. This fall, students in her class, HFS 400: Healthcare Communication, studied works from the Syracuse University Art Museum‘s collections to discover how art can deepen their capacity for sensitive, compassionate patient care.

“In the age of AI, these kinds of classes become more important,” says Cameron, whose collaboration with the Art Museum was supported by their Faculty Fellows program. “This art-centered teaching method strengthens [students’] core humanistic and cognitive skills. The uniquely human skills of interpretation, narrative building and empathetic understanding become even more central to professional identity, which AI can’t do.”

Visual Thinking in Health Care Education

Inside the Art Museum, Cameron’s students aren’t just viewing paintings. Instead, they’re practicing the observation and listening skills that will one day help them in the real world. Students select works of art that represent one of medicine’s most difficult moments: death notification.

In the clinical setting, death notification, or the process by which medical professionals inform family members or loved ones that a patient has died, is considered one of the most difficult and emotionally challenging tasks health care providers must perform.

The approach draws on visual thinking strategies (VTS) increasingly adopted by medical schools nationwide. Rather than memorizing facts, students learn to carefully observe, interpret multiple perspectives and communicate effectively—skills directly transferable to patient care.

Research published in the journal BMC Medical Education indicates VTS-based interventions consistently help develop crucial clinical competencies, with several studies showing statistically significant improvements in observational skills among medical students and residents.

For Sophie Heieck ’26, a pre-med student who plans to pursue a career in pediatrics, the museum experience has taught her something textbooks cannot. “As someone who is very fast paced and always on my toes, it was extremely beneficial to slow down, and really tune into my senses and what I saw and interpreted from what I was looking at,” says Heieck. “Medicine can be really fast paced at times and can often leave patients feeling like a number or a statistic. It is important to build that rapport with them.”

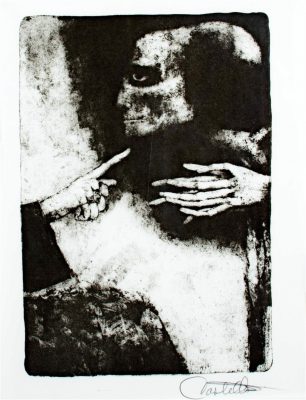

Heieck, who aspires to become a physician in her hometown of Geneva, New York, and to address health care disparities there, selected artwork portraying a poignant final moment between a loved one and the deceased.

After reviewing Federico Castellon’s work “Stop Him & Strip Him I Say,” she reflected on how it reinforced the importance of respecting grief and recognizing that individuals cope with loss in different ways—insights essential for delivering difficult news.

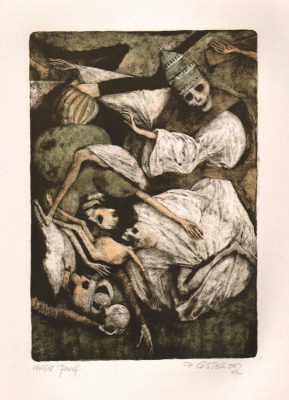

Sophia Kuber ’26, an HDFS major who plans to pursue a doctorate in occupational therapy after graduation, had a similar revelation. She chose to analyze Castellon’s “And the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all,” a work that explores universal themes of mortality.

Reflecting on the piece, Kuber noted how it shaped her understanding of death—revealing that cultural and personal beliefs influence how people perceive it. She observed that many

interpret death as a shared destination, a concept reinforced by the artwork’s depiction of bodies intertwined, evoking both the physical reality of burial and the symbolic unity of life’s end.

“This style of learning has allowed me to view heavily discussed topics in this course in a new light,” says Kuber. “Art has given me a new perspective on issues such as death notification that I would not have been exposed to without the help of the SU Art Museum.”

Through her analysis, Kuber discovered how cultural background shapes how people perceive death—insights directly applicable to patient care. “This experience will allow me to use what I learned to consider different perspectives of all medical situations and help me re-evaluate my decision-making for all patients in the best way possible,” she says.

“A lot of research and practice shows that our empathy tends to dip in health care profession training and medical school,” says Cameron. “So one of the benefits of leaning into the patient experiences is really honing your skills of observation and perspective taking.”

The pedagogical innovation aligns with recommendations from the Association of American Medical Colleges, which emphasizes competencies that extend far beyond scientific knowledge. Students are learning to be better observers and interpreters, developing health care communication skills they’ll use not just with patients and families, but also within health care teams.

“We’re unlocking these new ways of thinking and processing, which enhances their abilities and their skills,” says Cameron.

For their final project, students will present the artwork they’ve chosen, explaining how it captures themes of health care communication and death notification. The public is invited to attend the presentation on Dec. 9 at 9:30 a.m. at the Art Museum. The exercise transforms abstract concepts into visceral, memorable understanding—exactly the kind of deep learning that prepares students for the emotional complexity of real clinical settings.

Cameron’s course demonstrates the power of collaboration across the University. She partnered with Kate Holohan, the Art Museum’s curator of education, who helped design the curriculum and lead the museum sessions. Holohan’s expertise in using art for VTS and object-based learning was pivotal in creating meaningful interactions between students and artworks. This cross-disciplinary partnership—bridging health sciences and arts education—shows how shared university resources can spark innovative learning experiences.

Connecting With Pediatric Patients

Building on this foundation of experiential learning, Cameron is developing another innovative program: a teddy bear clinic scheduled to launch in fall 2026 at the Museum of Science and Technology (MOST) in Syracuse. The initiative will teach pre-health students to communicate effectively with pediatric patients by using play as a teaching method.

“One of the really well studied and well applied practices is play as an approach to teaching and learning for children,” Cameron says. Students will learn developmentally appropriate approaches to communicating about health topics, from explaining what a stethoscope does to preparing children for procedures like getting stitches or an IV.

“Our students will be using play to teach children around very general and basic introductory topics,” says Cameron. “The teddy bear becomes the patient.”

The clinic will feature different stations at the MOST, which already hosts health-related educational programming for the Syracuse community. Local families will be invited to bring their children and their favorite stuffed animals to learn about health care through interactive play, while Syracuse students practice crucial communication skills in a low-stakes, supportive environment.

Cameron credits support from A&S’ Engaged Humanities Network (EHN) for helping refine the project. As part of the Engaged Courses initiative, she receives funding and cohort-based pedagogical and logistical support to help her students apply their scholarly knowledge and skills to serve the public good.

“It’s really a collective of thoughtful faculty who are intentionally designing courses with students and our community in mind,” she says. EHN’s cohort meetings provide opportunities for faculty to share insights and receive feedback that strengthens their teaching approaches.

Real Skills for Real-World Impact

Both initiatives reflect Cameron’s core mission as a professor: preparing students for the health care field by connecting theory to practice through simulation and real-world experience.

“My main goal is to orient our students to the field of health care,” Cameron says. “And so a lot of it is theory and evidence. But we take it to the next step and allow them to apply what they’ve learned.”

As AI continues to transform health care delivery, these experiences are a reminder that medicine remains fundamentally a human endeavor. The ability to comfort a grieving family, to explain a diagnosis with clarity and compassion, to recognize the unspoken fears in a child’s eyes—these are the skills that help clinicians provide truly excellent care.

For Syracuse students preparing to enter health care professions, the path forward involves not just mastering technology, but cultivating the irreplaceable human capacities that make medicine an art as well as a science.